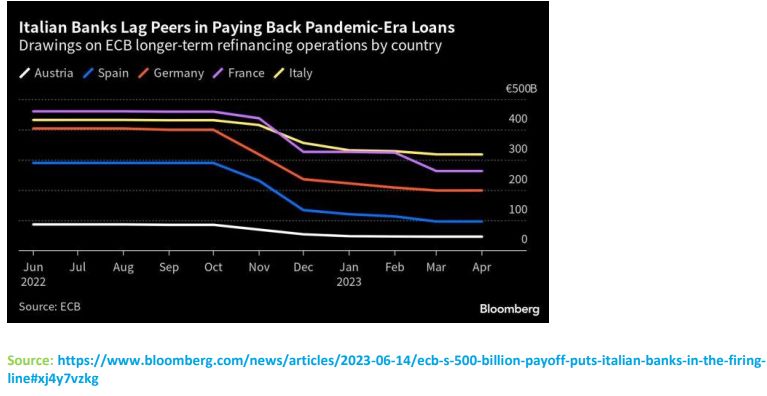

The European Central Bank is about to test the resilience of the continent’s banking industry by making lenders repay about half a trillion euros in cheap pandemic-era loans — in one go.

Italian banks may need to raise about €35 billion in 2023, and another €75 billion to prepare for more targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) loan repayments next year.

While the €4 trillion or so of excess liquidity sloshing around the financial system should limit the overall impact of the giant repayment, individual firms and countries could be strained, economists and analysts say. Smaller Italian lenders are the biggest concern, with Greek banks not far behind.

Background

Italy’s outstanding borrowing under the ECB’s TLTRO program is more than the excess cash its lenders have parked at the ECB, meaning some of its banks will have to raise money elsewhere to repay the loans. Greek lenders’ excess reserves are more or less equal to what they owe the ECB.

As €476.8 billion of TLTRO loans come due on June 28, economists believe that specific firms in Germany, France or other euro-zone nations could also feel the pinch.

The ECB’s own officials have concerns about the knock-on impact of higher borrowing costs on lenders with the most limited access to the money markets. Andrea Enria, the ECB’s banking supervisor, said last month that some firms have a “material reliance” on TLTROs.

ECB’s next steps

Analysts doubt that the ECB would introduce a new facility to tide banks over, even if they did find themselves locked out of private funding markets. Most economists polled by Bloomberg this month said they didn’t expect the ECB to offer fresh longer-term funding after TLTRO’s demise.

The central bank’s hands are tied by the vast amount of excess liquidity that’s already weakening the impact of monetary tightening. Even after more TLTRO repayments and the ECB’s shrinking bond portfolio are taken into account, excess liquidity could be roughly €3.5 trillion by the end of 2023, all else being equal. That’s only about 15% lower than current levels.

ECB President Christine Lagarde also seemed to play down that prospect after the central bank’s last policy meeting, saying that its standard facilities remained available. She was referring to operations that provide liquidity on a weekly and three-month basis: the main refinancing operations (MRO) and the longer-term refinancing operations (LTRO). Interest on those facilities is 50 basis points above the ECB’s

deposit rate, and smaller lenders forced to use them after paying off TLTRO loans would suffer a drag on profits.

Because of that, not everyone has ruled out the ECB stepping in to support struggling banks, even if the provision of fresh liquidity does appear to run counter to the fight against inflation.

Conclusions

The good news is that lenders have plenty of options for alternative funding: one being the repo market, where firms lend to each other on a secured basis. Banks may also turn to the bond markets to plug any gaps or choose to pocket cash from maturing bonds they hold.

Italian banks seeking cash in the repo markets — where collateral such as government securities can be pledged in return for liquidity — may find plenty of willing lenders, as liquidity remains so elevated.

Nonetheless they’d still need to offer a sweetener to attract funding, according to UniCredit strategists, who see Italian repo rates rising toward 5 to 10 basis points above the ECB’s deposit rate, the market benchmark.

COMMENTS